Chapter 1

What is Data Capitalism?

First let’s talk about capitalism and how it affects you.

If you live in the United States, you live in a capitalist country. This means you’re supposed to give money and get goods and services in return.

In an ideal world, this is a fair exchange. You pay what the goods and services

are worth to the worker who produces that good or service.

But that’s not how it works.

Capitalism is extractive.

You’ve probably noticed that when you buy things, you often pay money to a big company or corporation. And while that corporation seems to get richer, their workers don’t. That’s because the corporation keeps some of the money and gives the worker less.

No matter if you’re the worker who’s selling your time or the consumer who’s paying more because the company is taking a cut, corporations are always looking for ways to make more money off of you.

Using data, companies can extract even more from us.

How do companies decide how little to pay their workers and how much to charge you? They use data!

Nowadays, there’s a LOT of data that’s available about you and everyone else. Most likely, corporations are taking your data without your knowing. And they’re taking a lot.

Every time you shop online, engage with social media, or clock in for a shift at work, companies use data to target you and make them more money.

Your data is profitable to companies in a lot of ways.

For example, some companies sell your data to other companies. In this situation, you become the good or service sold.

Sometimes they make money off of you by making you pay more for something like a car loan, student loan, home loan, or business loan. How? By using an algorithm, step-by-step rules for a computer to follow to make a calculation,

solve a problem, or complete a task. The company ran your data through the algorithm, which made a judgement about you.

You lose out while the company pockets a bigger profit.

The algorithm tagged you as someone the company can get away with charging more or tagged you as someone with a “risky” background so they won’t show you the best deals. You lose out while the company pockets a bigger profit.

Some companies use data to target you as a worker. Using data to find efficiencies and optimizations means they can pay workers even less. Companies use data to calculate “optimum work schedules” that often result in you and your coworkers losing access to certain benefits and helping companies keep profits in their pockets.

This is Data Capitalism.

All these ways that companies use data to preserve the power imbalance in capitalism that keeps them rich and cheats the everyday person is data capitalism.

Chapter 2

Slavery, the Origin Story

Data capitalism is rooted in oppression.

Data capitalism, like capitalism itself, reinforces dynamics of power and profits. More power creates more profits, and more profits creates more power. Inequality ensures companies get richer and more influential, while everyday

people wield less and less power.

This loop is built off the original foundation of our country’s economy—slavery.

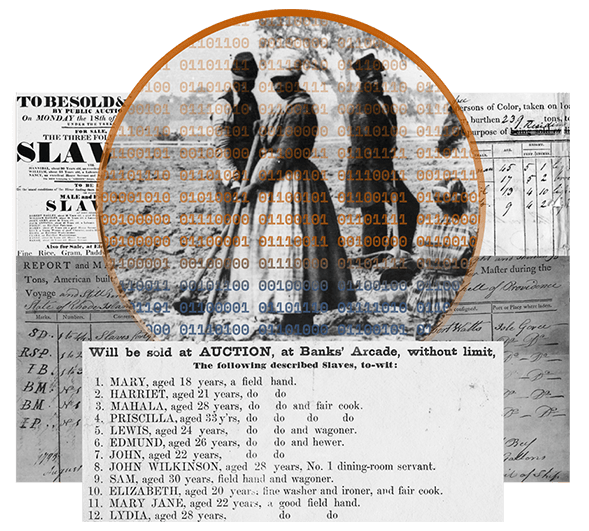

Slavery was the original method by which corporations commodified people for profit.

To make this horrific and immoral global system work, the slave trade corporations relied on massive data sets.

Slave traders and plantation owners tracked data on and shared data about their slaves in order to maximize profits.

They calculated things like increase, decrease, purchase, sale, death, appreciation, and depreciation of enslaved people. This use of data further dehumanized people in a system that already took away their freedom, humanity,

and agency.

Society as a whole has affirmed this racist core of data capitalism.

Although data capitalism was built by corporations, the government and those who hold power determine how it plays out. Together, their actions determine who data capitalism harms and who it benefits.

In the U.S., that means that data capitalism skews towards benefiting white wealthy people and a government that looks out for them.

Slavery ended, but the oppression of Black people for profit did not.

By the early 19th century, much of the western world had declared slavery morally unsound. The U.S. took longer to end slavery. After a bloody civil war, it finally did in 1865.

But the dehumanization of Black people, a concept born in slavery, was still very much present in the minds of government and white society. That’s why this country has a history of racist culture and policies, like segregation, Jim

Crow laws, Black Codes, and a racialized war on drugs that continues to this day.

Oppression was profitable. At their strength in the 1600s and 1700s, slave trade corporations were worth more than what Apple, Google, and Facebook are worth today...combined.

So it is unsurprising that companies found new ways to oppress Black people for profit after slavery ended. Throughout history, corporations have adjusted data capitalism to maintain their hold on the loop of power and profits.

The government and white society enabled these efforts or else turned a blind eye.

After slavery, using these racial divisions for profit became less explicit but still devastating.

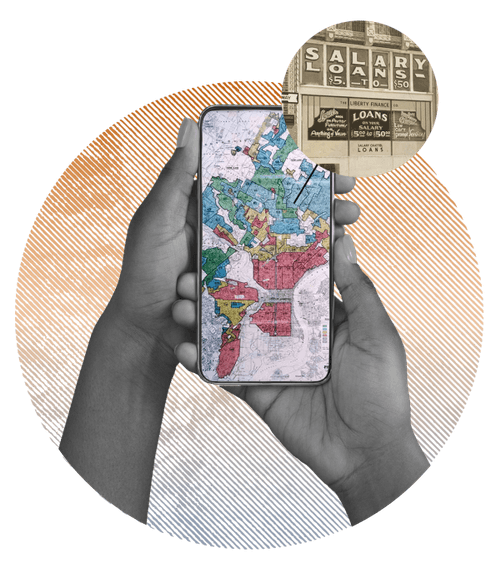

For example, in the 1930s, corporations updated their tactics and started doing something called redlining.

Banks realized that they could make more money if they only gave loans to “worthy” people who lived in “good” neighborhoods. If you lived in a good neighborhood, you could get a loan.

But good neighborhoods were all white. Bad neighborhoods were highlighted in red on maps so bankers and investors knew not to give loans there. They didn’t directly say “if you’re Black you don’t get a loan,” but they did say “if a Black person lives in your neighborhood, then it’s a bad neighborhood. And if you live in a bad neighborhood, you don’t get a loan.”

The legacy of redlining lives on; 74% of the neighborhoods labelled “bad neighborhoods” by banks from redlining are today the lowest income neighborhoods in America.

And these neighborhoods are still predominantly non-white.

Today, racialized oppression is still profitable.

Corporations have access to a lot of data about us. They use that data by putting it through algorithms that can analyze millions of data points in a matter of seconds. That means they can prey on these racial divisions even faster than

before.

Using “race-blind” data and algorithms still creates racist results.

While corporations claim that they are building algorithms that are “unbiased” or “race-blind,” these algorithms use data that has the racism of our society embedded in them.

For example, many companies use data points like zip codes or wealth to make decisions about how much to charge certain people. But, these variables have the history of redlining embedded in them. Using them produces racially biased

results.

When companies use an algorithm and its results reproduce and spread racial disparities, they create algorithmic racism. To address algorithmic racism, corporations must know and think about the history of injustice and inequality rather

than overlooking it in an attempt to be “race-blind."

The racism of data capitalism was intentional, but it’s not inevitable.

Coming from the starting point of slavery, it is clear why data capitalism continues to perpetuate racial inequality. But that doesn’t mean we’re powerless to stop it.

Chapter 3

Stories of Resistance

Can we overcome data capitalism?

Yes! Getting here took intentional actions, decisions, and policies. So we can use intentional actions, decisions, and policies to get us out.

The fight has already begun.

Here are three stories about how organizations and individuals are breaking the loop between corporate profits and our data.

Choose one of the stories below to learn about how workers refused to be tracked by Amazon, how people took Facebook to court over racial discrimination in ad targeting, or how journalists uncovered racist algorithms in the car insurance market.

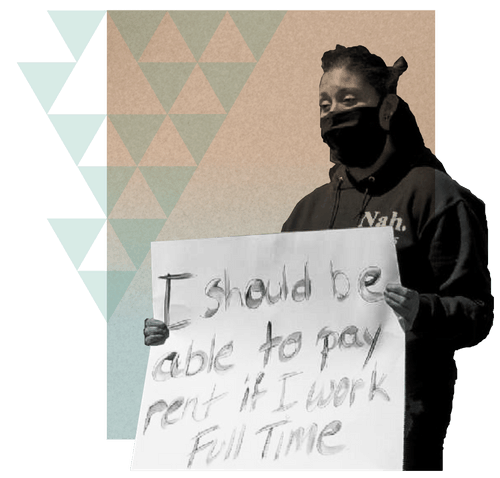

Workers refusing to be tracked by Amazon.

Amazon requires delivery drivers like Adrienne to download and continuously run a smartphone app called Mentor. Mentor tracks drivers and gives them a score based on a set of unknown criteria. Numerous drivers claim the scores can be faulty and difficult to contest. Yet this one score determines a lot,

including pay, for the predominantly Black and brown field and customer support workers.

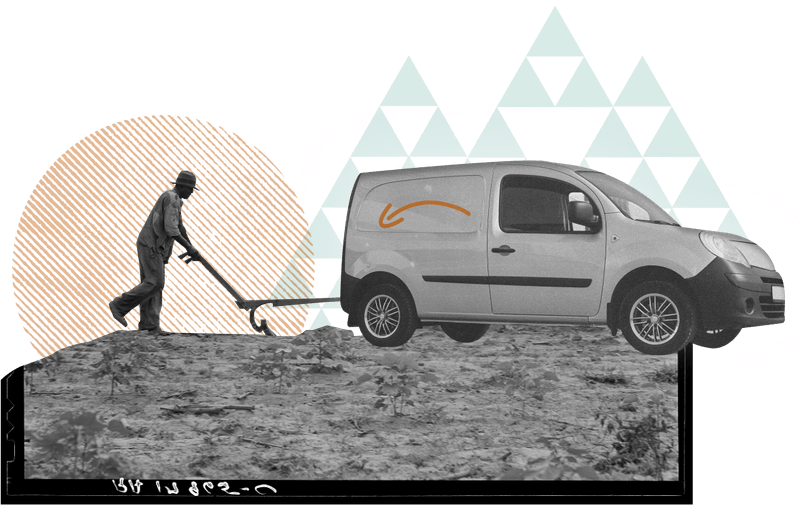

Amazon’s constant tracking of their workers evolved from centuries of dehumanizing practices, practices that began in slavery. There is no doubt that slavery was incomparable in its brutality. Yet these practices continue

to serve as a blueprint.

For example, after slavery, many recently freed slaves became sharecroppers. Though sharecroppers were technically free, sharecropping created a new system of entrapment.

Land owners would track sharecroppers’ every activity like how much they made and how much they sold. And then, they would always add in extra expenses. Sometimes sharecroppers would not be told what the expenses were until it

came time to settle up, keeping them guessing and unable to control their circumstances. These calculations often led to sharecroppers having more debt than profits, indebted to the land owner in perpetuity.

Today, apps like Mentor help big companies find ways to underpay productive workers. Mentor is glitchy, dinging drivers for things completely outside their control, like getting a call from a family member - even if they did not pick up the call. Drivers

say low scores can result in disciplinary actions, being taken off the work schedule, losing access to bonuses, and being removed from optimal delivery routes.

All of this is intentional. Amazon’s business model is based on controlling their workers, using data to supervise workers’ schedules down to every minute. It is no surprise that Amazon workers describe feeling completely dehumanized.

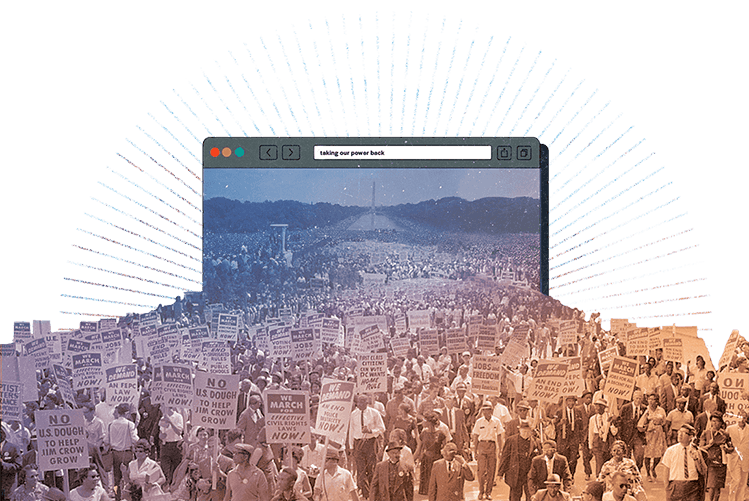

Amazon workers like Adrienne Williams are fed up. In May 2020, Adrienne organized a protest outside Amazon’s warehouses in Richmond, CA to demand change.

Adrienne is not alone. Amazon workers across the country are organizing. Over the past few years, Amazon workers from Minneapolis, Minnesota to Bessemer, Alabama have been leading

the movement to demand a seat at the table.

Adrienne is not alone. Amazon workers across the country are organizing.

In the fight against data capitalism, these efforts, led by Black workers, redistribute power into the hands of the people.

Taking Facebook to court over racist ad targeting.

A key part of Facebook’s business model is selling targeted ads. In theory, this means companies advertise to only those consumers who are most likely to buy their product. In practice, Facebook’s filters allow advertisers

to act upon the same racial prejudices in advertising that have existed throughout our history.

When people discovered this, they were outraged. Several organizations and individuals filed class action lawsuits against Facebook for discriminatory advertising practices.

Racial discrimination in advertising is not new. For over a hundred years after the Civil War, Jim Crow laws and segregation practices allowed businesses to use explicitly racist advertising, like posting “whites only”

signs in their windows. The size and scope of Facebook’s advertising reach makes it dangerous on a different scale.

Facebook’s platform allowed advertisers to filter out specific people shown an ad by “ethnic affinity,” effectively a category for race. What’s more, the ethnic affinity category only included categories for people of color, like “African American,” “Asian,” or “Hispanic.” White people were an unnamed default.

Regardless of whether you tell Facebook your race or ethnicity, Facebook collects your data (pictures, likes, groups) and uses a predictive algorithm to guess your race.

In March of 2019, Facebook settled the class action lawsuits about discrimination in advertising. In the settlement, they agreed to no longer allow advertisers to filter ads based on race, gender, or age.

Legal action has made a difference, but for lasting change we need oversight and regulation to prevent companies from profiting off of racism.

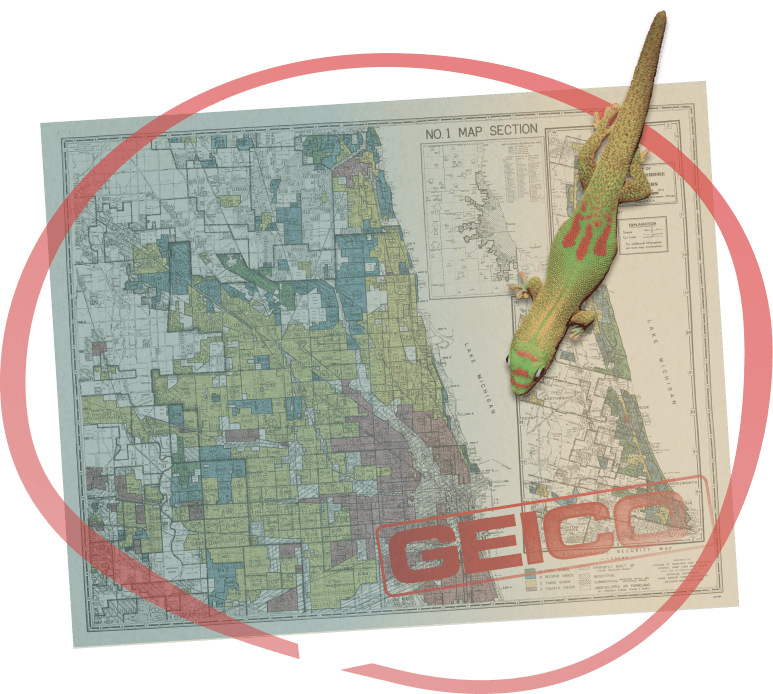

Uncovering racist algorithms in the car insurance market.

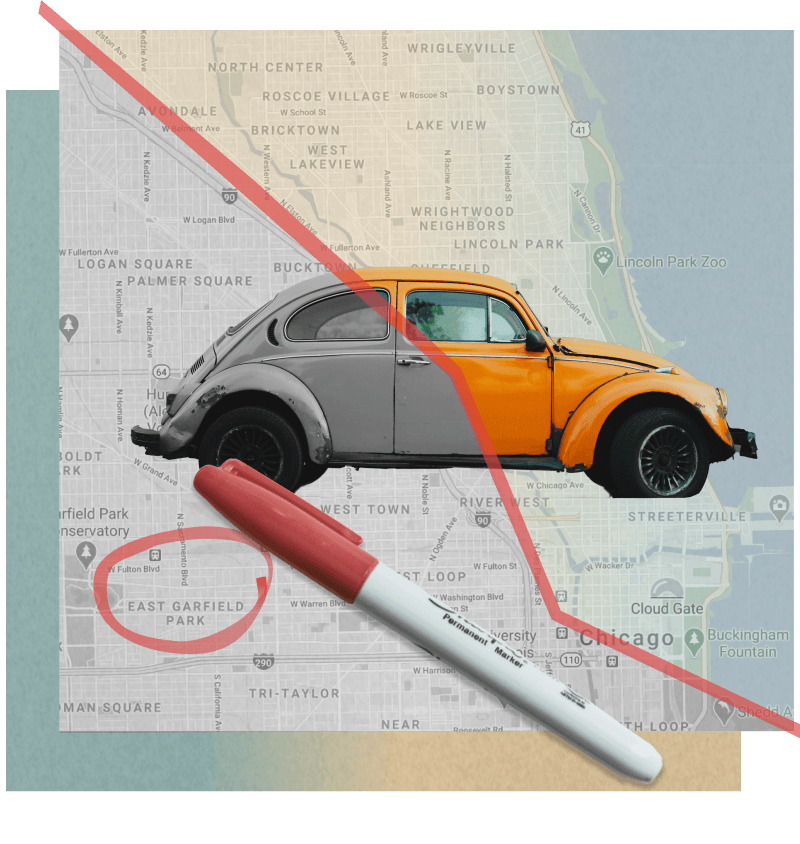

In 2017, journalists speaking to residents of Chicago started to notice an alarming trend.

In East Garfield Park, a primarily Black neighborhood, a Black resident was being charged $190.69 a month by Geico for car insurance. Across town in Lakeview, a whiter, more commercial part of Chicago, another Chicagoan

paid $54.67—even though the vehicle crime rate in Lakeview is higher than in East Garfield Park.

Car insurance companies are not transparent about the algorithms they use, but investigators at ProPublica and Consumer Reports got their hands on enough car insurance data to show that discrepancies in prices between Black and

white neighborhoods are too wide to be simply explained by objective risk factors.

The reporting by ProPublica and Consumer Reports showed that zip codes were a factor in the algorithms that determine insurance rates. We know that zip code data is laced with the legacy of redlining and segregation.

From the 1930s to 1970s, banks used redlining to deny Black people loans, marking Black neighborhoods in red to designate them as too risky for loans. Denying Black communities access to loans in the past led to the racial

wealth gap and continued residential segregation that exists today. Using zip code to determine insurance rates perpetuates the legacy of redlining’s racism.

Because car insurance companies do not willingly share their algorithms with regulators or the public, it is hard to make demands to address their algorithms' racist outcomes. We don't know if zip codes are the

only variable in the algorithm that's producing racist results or if there are other factors contributing to these disparities.

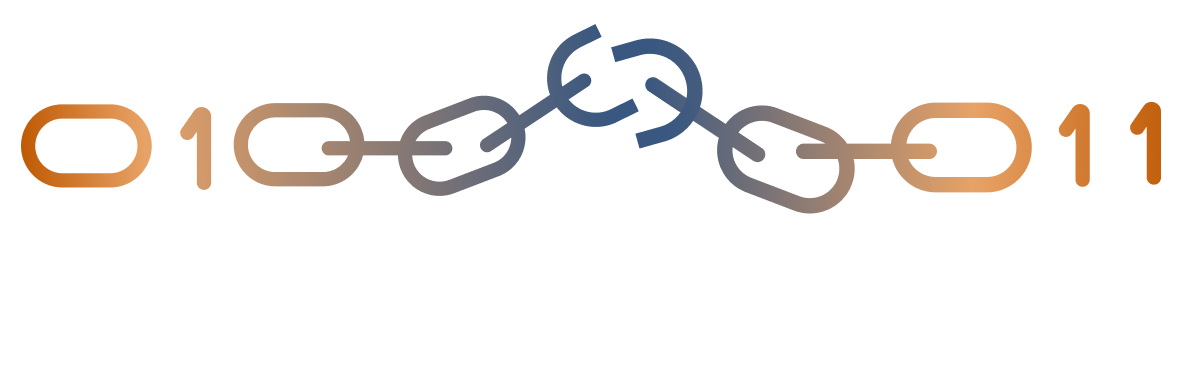

ProPublica and Consumer Reports have called out the link between corporate profits and our data, bringing us one step closer to breaking that link.

By knowing these algorithms exist and how they affect us, we can demand more transparency and democratic control over their application and impact.

Epilogue

Take Action

Reading this website is just the beginning.

Questioning the link between corporate profits and our data is the first step. If you read this website, you are already here!

Fighting back requires our collective efforts to be conscious, curious, and active in the fight against data capitalism. Help other people learn about data capitalism by sharing this website.

What else can I do?

This is a big problem and unfortunately there aren’t simple answers. Systemic problems require systemic change.

What’s next must be defined by all of us. When we share the website, the next step is the conversation we have with each other.

What can we all do together? What are the small things? What are the wildest ideas we can imagine? What would it look like for us to have control over our data and the algorithms in our lives?

Looking for more specific solutions?

Read our full report. The report gives even more examples of how data capitalism and its racist history affect us today, and includes dozens of technical and policy ideas.

About

This website is based on the report Data Capitalism and Algorithmic Racism by Data for Black Lives and Demos.

Data for Black Lives is a movement of activists, organizers, and mathematicians committed to the mission of using data science to create concrete and measurable change in the lives of Black people.

Website content, design, and illustrations created by Akina Younge, Deepra Yusuf, Elyse Voegeli, and Jon Truong. In creating this site, we aimed to meet AA accessibility standards so that the site can be enjoyed by everyone.

Report design, style, and illustrations created by David Perrin, Senior Designer at Demos.

Special thanks to all the users and Data for Black Lives staff who helped test and improve this website throughout its development.

Love this project? Stay in touch! Data for Black Lives can be reached at info@d4bl.org .

Photos used in illustrations are from National Archives, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Creative Commons, Flickr Commons, Pexel, Unsplash, Ketut Subiyanto, J. P. Moquette, Jernej Furman, Virginie Goubier, Norma Mortenson, Florida State University Digital Repository’s Florida Manuscript Materials R.F. Van Brunt Store Day Book, Dorothea Lange Farm Security Administration collections, Tony Webster, Terri Sewell, Tingey Injury Law Firm, govinfo, Ferris State University’s Jim Crow Museum, CLAIN Dominique, Kara Zelasko, Dan Gold, Kelly Sikkema, Steve Johnson, and Michaela Kliková.